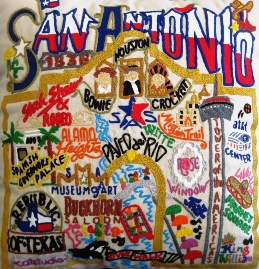

Things to do in Alamo City

SAN ANTONIO – I can see Alamodome from my window. It’s a mile southeast of where I sit, and its southwestern spire is visible between Henry B. Gonzalez Convention Center and Tower of the Americas. Alamodome’s history is interesting in a way that enkindles barbershop dialogues. Indulge me a bit.

Before he became the 10th secretary of Housing and Urban Development – and inadvertently fired the starter’s pistol on policies that brought economic ruin 15 years later – Henry Cisneros was a mayor enchanted by the idea of professional football in Alamo City. Build a stadium, his thinking went, and the NFL will come.

The city built Alamodome, but professional football never came (unless one counts the Saints’ 2005 refugee appearance after Hurricane Katrina). The local branch of University of Texas began its inaugural football season last fall, and Alamodome will have an Arena Football League team later this year. But you get the picture.

Saturday, happily enough, Alamodome will return to doing what it does well as any stadium in the country: host prizefighting. Two upcoming stars – one by inheritance, the other ingenuity – will headline the card. Nonito Donaire, the ingenious one, will make his super bantamweight debut against Wilfredo Vazquez Jr. And Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. will defend a middleweight title against Marco Antonio Rubio, using the patronym that set an attendance record at Alamodome five months after it opened in 1993.

Or perhaps Chavez-Rubio will be 2012’s best fight. Nobody knows how these things go. This city certainly does not and even if it did would be reticent to say so. That’s part of San Antonio’s special character. Its downtown area is an intriguing, maddening, wonderful snarl of Mexican culture and German industriousness – the sort of place that can provoke a comfortable type of marvel.

If you’re in town for fightweek, spend some time off the well-worn track. You’ll get a chance to see the Alamo, fear not; the weigh-in will happen in front of the place once known as Misión San Antonio de Valero, Friday. But there are four other founding Spanish missions within five miles of the Alamo, and each is a picturesque history unto itself.

If you travel with any sort of frequency, you’ve no doubt before made this proclamation: “I want to go someplace tourists never go!” Here’s a suggestion, then. Once you finish dutifully marching the commercial loop of River Walk, head west to the part of San Antonio River that locals use. Make a right and go north. You’ll find yourself beneath the country’s seventh-most populous city, surprised by its tranquility. Under each bridge you’ll see a unique installation by a local artist. Eventually you’ll come to historic Pearl Brewery where you can catch a ride home on a river taxi.

You’ll be back in your hotel with time for a nap before Saturday’s card. Get to Alamodome before 6:00 PM, though. Adam Lopez, our city’s best amateur, will make his professional debut on the undercard, beginning an adventure that will try to fill the prizefighting void Jesse James Leija left when he stopped fighting and started training. There’s another good place to visit, actually: Leija’s Championfit Gym is five miles up San Pedro Avenue and worth the drive.

The portion of the card televised by HBO – the first major event of the year – should be a pleasant departure from what the words “HBO Boxing” have come to connote with aficionados recently.

Nonito Donaire is what baseball scouts call a five-tool player. He is very large for a 122-pound fighter. He has speed, technique, and power in both hands. He must have a chin, too, though he rarely needs it.

That might change Saturday. Wilfredo Vazquez Jr. comes to fight. He is not large, quick or confident as Donaire, but he is the son of a Puerto Rican super bantamweight who made some history of his own in this city when, in 1995, he upset WBA world champion Orlando Canizales. Vazquez Sr. will be in his son’s corner, exactly where he was when Vazquez Jr. made one of 2011’s best fights against Jorge Arce. Expect Donaire to win, but expect him, also, to know he was in a fight.

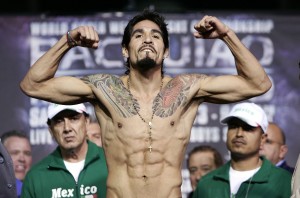

Whither the main event? It will be entertaining because Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. makes entertaining matches. He is not a natural like his father, but he is better than you think. He is technically adequate and improving under trainer Freddie Roach. He understands how combat works from having watched his father do it during the 10 years of Chavez Sr.’s prime. And best of all, Chavez Jr. gets pissed off when he’s hit.

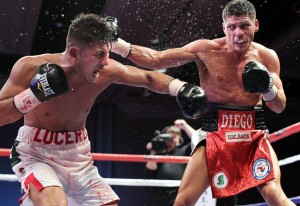

Marco Antonio Rubio should test Chavez early the way John Duddy did in Alamodome 17 months ago. Round the gyms down here, folks give Rubio a chance. That’s good; it’s what they’re supposed to do. We all did it with Duddy, Sebastian Zbik and Peter Manfredo. These were serious men, remember, more serious than Chavez anyway, we assumed, and they’d test his whiskers and balls. And they did, too.

And Chavez passed, too. Rubio’s talent is likely a day beyond its expiration date. His reflexes, canniness and desire to win probably went sour in 2011, but we don’t know it yet and won’t till Chavez opens the carton and takes a sniff. Chavez doesn’t know it either, and at the kick-off press conference he seemed unusually peevish about Rubio’s calling him out. Rubio is a fellow Mexican fighting before a partisan-Mexican crowd, too, so you never do know. But it says here Top Rank’s master matchmaker would never have Chavez postpone a reckoning with world middleweight champion Sergio Martinez to lose a fight with Marco Rubio.

Let’s end here: If you’re staying downtown this week and wish to visit a legendary local spot, come by San Fernando Gym any weeknight and honor the memory of the late Joe Souza.

Bart Barry can be reached at bart.barrys.email (at) gmail.com