They can’t all be Izzy and Rafa

By Bart Barry-

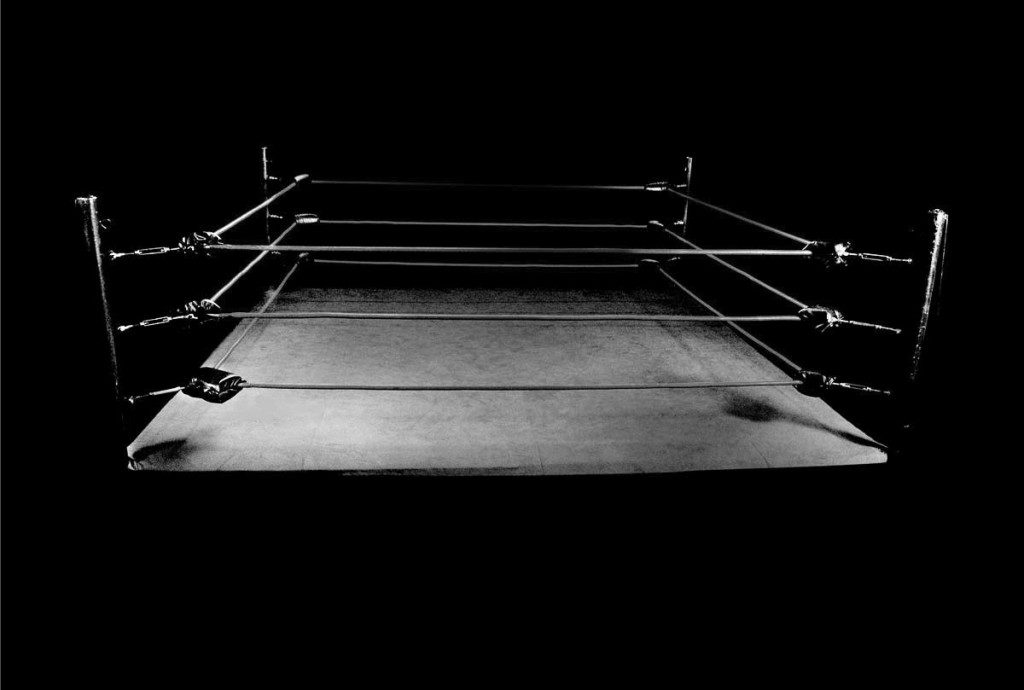

Thursday in the co-comain event of a Super Bowl

week fightcard broadcast by DAZN from a shady Miami venue called Meridian at

Island Gardens – check out its Google reviews for a chuckle – super

bantamweight Danny Roman lost his WBA and IBF titles by split decision to Uzbekistan’s

Murodjon Akhmadaliev in a very good fight worthy of a rematch.

They were there to make history, history be

damned. Akhmadaliev was to break Leon

Spinks’ record, a record few knew existed till DAZN’s promoter unearthed it, and

if that meant the benefit of most every scoring doubt need go the Uzbekistani,

so be it. Thursday evening’s co-comain

fare was very good, again, but not historic, even if everything broadcast these

days must be.

WBA

Scores Analysis, which seems founded on innovative logic, got the score

right, Roman 115-113, by weighing the three official scorers against each other,

in an ode of sorts to selforganization. There

are far worse analysis tools out there.

Writing of which, punch statistics, too, appeared

to favor Roman, even if prefight research should indicate Roman did not strike Akhmadaliev

nearly so hard as he got struck by him. That’s

the thing about research, though. What

evidence did the eyes perceive that Akhmadaliev hits so much harder? His was the more marked face at final

bell. His was the much more fatigued

body for three minutes before final bell.

And most replays showed him flurrying like a teenager whenever at close

quarters, pepperdusting Roman’s elbows and wrists and collarbone.

Akhmadaliev was not the better prizefighter in

Miami, and Roman, the unified champ, did more than enough golfing Akhmadaliev

with uppercuts to retain his titles on a traditional scorecard.

A note about that.

Close rounds traditionally get scored for the champ, not the challenger,

because that’s where the eyes fall before each engagement. I’ve written about this a few times before,

but even if you’re tired of reading it, methinks, I’m not yet tired of treating

it:

A truly objective scorer should begin his eyes in

the neutral space between the fighters and return his eyes to that space often

as possible, too. From that neutral

space he should track any punch that crosses the threshold and grade its effect

thereafter.

Impossible, you say? Quite right.

There are no truly objective scorers.

The fighter upon whose fists a scorer’s eyes most

frequently fall has an appreciable scoring advantage, sort of like, and for

much the same reason, the actor upon whom audiences’ eyes most frequently fall

has a scoring advantage at the Oscars.

In performance arts they call it presence, and in prizefighting it be

the champion’s gree to lose. Except when

marketing or gambling concerns make it otherwise.

Such was the case Thursday when the barely tested Akhmadaliev

entered the ring with marketing and gambling concerns in his favor. Of those two, of course, the gambling

concerns always be more honest, and the chalk had it that Akhmadaliev was

probably something very special while Roman was already something a bit

journeyman.

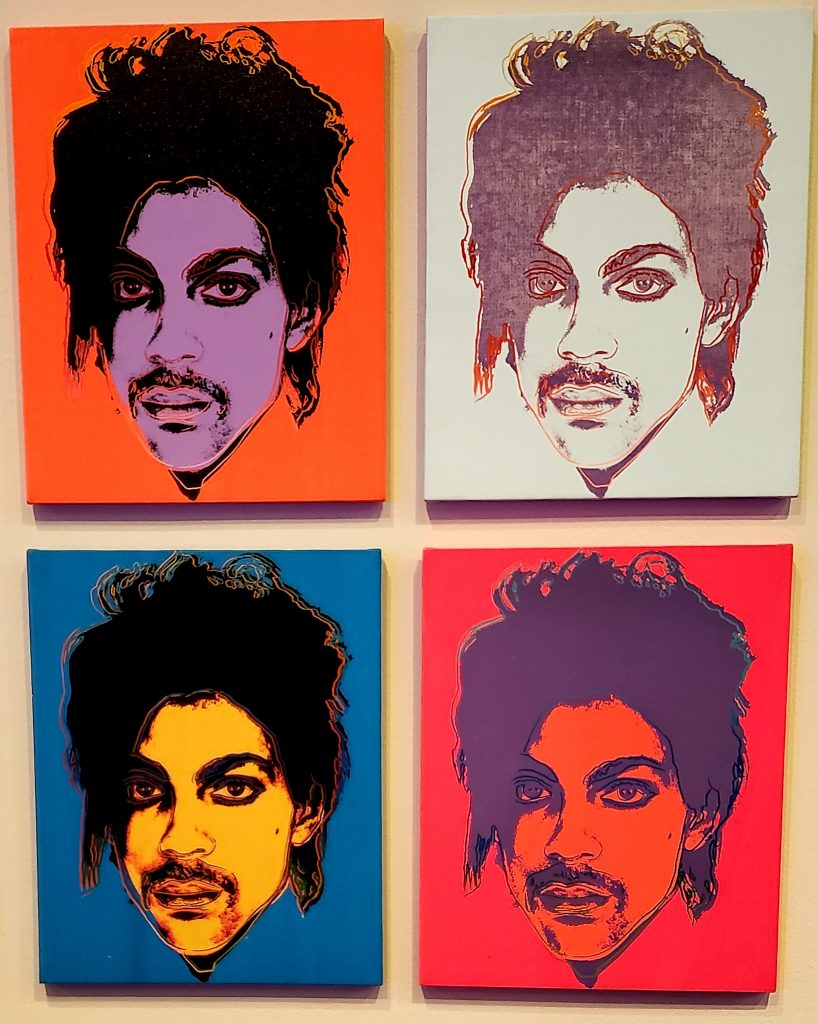

Instead, Akhmadaliev was a cross between Ukraine’s

Vasyl Lomachenko and Armenia’s Vic Darchinyan, and not the right cross

exactly. Were a man to mix successfully Lomachenko’s

form and Darchinyan’s aggression he’d be a historic entity. Trouble is, Akhmadaliev more often mixes Darchinyan’s

form – back elbow cocked for telegraphing – with Lomachenko’s aggression,

ballrooming his way away.

There’s a whiff of autoheadline-reading there; Akhmadaliev

believes he is more than he is by virtue of his historic career, and for reasons

both financial and patriotic nobody round him has yet to say it isn’t so. Danny Roman kinda said it in round 12,

though, didn’t he? Whilst Akhmadaliev tried

Will-O’-the-Wisp-ing his way to winning a round without throwing a punch for

its opening 5/6, Roman did the needful, as they say, walking forward and

winning the closing round with classic boxing.

O, but look how much Akhmadaliev did in all the

preceding rounds! Yes, do.

Thursday’s fight was a modernday Vazquez-Marquez,

was it not? Larger money, lower stakes, poorer

form, lighter punching, less conclusive ending.

They aren’t making 122-pounders like Izzy and Rafa these days, even if

they’re commentating like they are.

Still, as Super Bowl fightcards go, this wasn’t a

bad one. Skipping the amateur boxing on

the card, half the televised matches were good and competitive.

Twelve years ago I covered a Scottsdale, Ariz.,

card the week of Super Bowl XLII and the week before that a local promoter told

me: “They always try to do Super Bowl week, and it never works.”

That wasn’t the best quote, though – that came

from “El Machito” Hector Camacho Jr., on the card to supply a patronym fiftysomething

East Coast lushes might recognize and pay some slight fraction of what $10,000 the

card’s visiting promoter initially thought he might charge for ringside seats to

a Monte Barrett mainevent in a converted carny tent called 944 Super Village at

Stetson Canal.

“I’ve disrespected the sport of boxing so many

times I’m surprised they let me put gloves on,” said El Machito (44-3-1) at the

Friday weighin, by way of promoting his Saturday afternoon battle with Luis

Lopez (13-11-1).

The reason Super Bowl week fightcards generally

don’t work is because while the Super Bowl attracts men in shiny suits, they’re

bespoke suits, generally, and boxing is decidedly off-the-rack. By the magic math of a visiting promoter

there are at least 10,000 guys in town who could care less about $10,000, and

if he can just find 20 of them he’s on his way, 50 of them and he’s the new Don

King (who posted a Super Bowl XXX loss of his own 24 years ago in Phoenix on a

card that included famed ticketseller B-Hop).

Shiny suits and carnival barking.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry