The funniest men on the planet

By Bart Barry-

Saturday at Madison Square Garden in a fight

broadcast by DAZN, statuesque world heavyweight champion Anthony Joshua and misshapen

challenger Andy Ruiz made quite possibly the funniest spectacle in our beloved sport’s

history. If you weren’t laughing or at

least smiling you missed one of life’s unique opportunities, and if you were

among others who weren’t laughing with you, why, you must improve your

associations immediately.

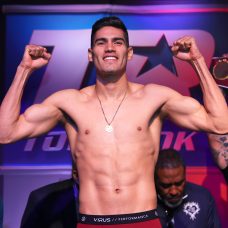

Chubby Andy Ruiz, brought in on short notice for a

ritual humiliation with the baddest man on the planet, razed Joshua a fourtime,

made him a passive round-7 quitter, and humiliated the whole of boxing’s heavyweight

institution.

The moment was ecstatic. As ringside commentators and scribes readied

their solemnest tones to impart the historic import of what just happened, the

DAZN replays, hyper-definition hyper-slo-mo showed the challenger’s back,

jiggling pornographically, as he put the finishing touches on AJ. It was a form of visual comedy whose

authenticity someday may be matched but cannot be topped. It was a sight so wondrous a child couldn’t

miss its absurdity and any right-thinking adult had to enjoy it a hundred times

more for its rarity.

Joshua, to his credit, laughed through the entire

episode; perhaps the absurdity enchanted him, too, or perhaps he was knocked

silly or perhaps longsuffering aficionados called for comeuppance in a single

voice and for once the universe heeded us.

It was not a joke on Joshua so much as his enablers. The selfaggrandizing fleshpeddlers and

circusbarkers, the celebrity tourists and their publicists, the vlog buffs and

podcast critics and every dweeb with a calculator app and pay-per-view

prediction, the lot of them, didn’t know enough to laugh – didn’t realize the

moment called for joyful selflessness, for losing oneself not in Ruiz’s triumph

but in our sport’s absurdest moment.

“Honest to God, he’s going to lose to Ruiz.”

“AJ’s going to get caught with a lucky punch?”

“Nope.”

“He’s going to separate his shoulder or sprain his

ankle?”

“Not even close.”

“He’s going to get robbed by Yank judging?”

“Colder.”

“I give up.”

“Fully able to continue, after getting spanked and

sparked by an obese lad over whom he towers, Joshua’s going to spit his

mouthpiece, retreat to a corner and refuse to defend his four titles one second

longer.”

Part of the ecstasy of the moment was its impossible

unpredictability. Even if a wiseacre or

innocent among us bothered to pick Ruiz on a lark, not even he might’ve

predicted Saturday’s final instants: Joshua’s taking a knee, enduring another

count, rising robotically, retreating to a corner, refusing to toe the line,

telling the referee he wanted to toe the line, reclining further in his corner,

refusing to toe the line, telling the referee he wanted to toe the line,

watching the referee wave hands in front of him, feigning a momentary disgust, resigning

himself, reclining once more.

Joshua’s hardest fight was with disbelief much as Andy

Ruiz. Told his entire career what a

business he was, how many livelihoods he sustained throughout the kingdom, how

groundbreaking be his brand, AJ waited patiently for some institutional

intervention; his majesty requested a sabbatical in round 7, and only the

grandest act of ingratitude might deny it.

Then it happened – his request got declined. As you read this, whether on the day it is

published or 10 years later, Joshua still can’t believe his request for recovery

time got rejected.

Do you have any idea who I am?

It’s funnier still to know, as we all now do, his

request for sabbatical, if granted, wouldn’t have changed anything but the

official time of stoppage. Joshua was

beaten in round 3, not even a halfminute after dropping Ruiz with a dandy

hook. Ruiz rose, confused, while

something like the word “inevitable” went through every bystander’s mind at

once. It was, then, time to train our

eyes on Joshua, the better to observe how quickly he took Ruiz’s consciousness,

compare it in real time with our recollection of what Deontay Wilder did a few

weeks back, and birth a fully formed conclusion on who would win the

hypothetical match between them.

And then in the middle of the sacrifice Saturday’s

scapegoat nipped its highpriest. Just a

nip, truly, a balance shot but nothing a baddest man on the planet should register. Then the entire artifice came down in a laughable

heap, rose, then came down again and again.

We can leave the serious analysis to anyone who still takes any

heavyweight seriously but drop a breadcrumb as we skitter away laughing: Ruiz

nearly broke Joshua in half with a midrounds right cross to his midsection that

dropped the champion’s left guard surely as fatigue dropped the champion’s full

self, and that tells you the wisdom of Joshua’s wanting an immediate rematch.

How damnably fragile be these giants! Ten punches in his finishing move Joshua was

suffocating, heaving his gorgeous pecks and regal delts, pleading Manhattan

thicken its air. What the hell kind of

professional fighter finds himself drowning 10 punches in to a fight’s ninth

minute?

It added to the moment’s high mirth, though, it

did. The fatman’s shimmying pursuit, the

giant’s ridiculous retreat, the most important arena in the history of

important arenas gone muted, the imperial palace reduced to what red sauce and

orange cheese cover an enchilada plate.

The spectacle was relentless fantastic. The champion tagged and toothless, his mouth

alternating between airsucking ovals and get-this! smirks, the champion’s

boundless selfassurance swapped in a realtime identity crisis (how about that

ridiculous bouncing-n-boxing thing in round 6), and all for our entertainment. Sport can be no more entertaining than

Saturday’s main event. If you’re new to

boxing be grateful you’ll have a standard of comparison the rest of your days,

and if you’re old to boxing be grateful you lived long enough to witness the

funniest moment of the modern era.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry