TEMPLE, Tex. – Sometime after this town was created in 1881 by the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway Company, folks riding the trains in and out of its depot gave it a few creative nicknames. Some called it “Mudville” for the nature of its soil; others called it “Tanglefoot” for its ungoverned frontiersman spirit; and a couple even called it “Ratsville” for the creatures that populated it.

Don Escobar, a 31-year-old lightweight who kicked-off a seven-match “Mayhem at the Mayborn” card Saturday night, must wonder why the last nickname ever went away.

Escobar made his second professional fight, at the Frank W. Mayborn Civic & Convention Center, a few miles north of Temple’s towncenter, on Saturday, and for the second time in his career faced a hometown favorite. Jerry “The Flash” Fuentes, making his professional debut, beat Escobar by technical-knockout at the 0:59 mark of the fourth and final round.

But this is boxing, of course, so it’s never that simple.

Escobar fights out of San Antonio, 145 miles south-southwest of Temple. While Escobar and Fuentes are both Texans – and therefore expected to get the benefit of every doubt from Lone Star State officials if they fight a guy from, say, California – Texas is an awfully big state. Figuratively, then, Escobar hailed from another country when he met Fuentes.

Why the hell was I 2 1/2 hours from home to watch a card comprising fighters with an aggregate record of 25-40-11? For a chance to visit Opie’s BBQ in Spicewood, yes, but that’s not all. I also wanted to see Temple’s “Ironhorse District” featuring the Railroad & Heritage Museum. Oh, and one other thing: I consider Don Escobar a friend.

Escobar is a fighter in every sense of the word – good and bad. He divides his training time evenly between two San Antonio gyms, Morones Boxing House of Champions and San Fernando Gymnasium. He trains himself for the most part, relying on tricks he learned 10 years ago in the military – boxing at Fort Huachuca, Sierra Vista, Ariz. – and years later from a guy named Joe Souza.

Escobar likely gave his best years to sparring. As an amateur he never committed quite the way he might have.

“I was a single father of two boys, you know?” he says, by way of explaining why his amateur record was less than his talent said it should be. “I couldn’t be traveling everywhere they wanted me to.”

He turned pro in October and promptly lost a majority decision in Laredo, Tex., to a fighter from Laredo, Tex., by interesting scores of 35-40, 37-38 and 38-38.

He got a bit discouraged – face marked up, nose busted. But he’d made a good fight; his manager had no trouble finding him another b-side gig 300 miles north of Laredo in Temple 106 days later. He struggled with weight, calling himself a “tropical fighter” whose body’s misbehavior is indirectly proportionate to the thermometer’s mercury. He was seven pounds above the lightweight limit on Wednesday and came in at 136 1/4 on Friday’s official scale.

Jerry Fuentes, meanwhile, made 134. And Fuentes’ 134 looked a lot more impressive Saturday than Escobar’s 136 1/4. Fuentes was the larger man, both taller and better muscled.

That was my first observation. It came shortly after a singing of the National Anthem and the reading of an interesting prayer by the ring announcer, one that called God’s attention to this fight-night detail: “If there are injuries, only minor ones.”

In the first round, and the three that followed, Fuentes also proved to be the better-conditioned athlete – for the opening minute. After that, though, Fuentes was Exhibit A of the largest difference between amateur boxing and prizefighting: A round in the pros is 50-percent longer. Fuentes allowed the smaller man to bull him into the ropes and work him over with body shots and grappling in rounds 1, 2 and 3.

Escobar also caught Fuentes with a combination of punches he’s come to call, simply, “The Marquez.” Named after Juan Manuel Marquez, probably the only prizefighter ballsy and talented enough to routinely throw uppercut leads in championship fights, “The Marquez,” when thrown by a southpaw like Escobar, goes: Right uppercut, overhand left.

Fuentes hadn’t seen many uppercut leads in sparring, especially from someone with his back on the ropes.

Checking my own likelihood of bias, then, I had those Marquez combos and Escobar’s aggressiveness making a tally of 2 rounds to 1 (29-28) for Escobar, with one round to go.

Then controversy struck. Fuentes came out his corner extra strong at the start of the last round of his first prizefight and rocked Escobar with a 1-2. Escobar’s head snapped up, and his body tossed forward. He wrapped Fuentes in a bearhug, and referee Danny De Alejandro broke the fighters. Escobar took a few steps back and set his hands to block Fuentes’ next assault. Fuentes threw a couple more punches, and De Alejandro leaped between the men and waved the fight off.

Temple’s Jerry “The Flash” Fuentes had a knockout for his pro debut.

Don Escobar lost himself. He shoved De Alejandro’s hands away and immediately accused the referee of favoring the hometown fighter. Then Escobar stormed out the ring and had his gloves pulled off before the fight’s result had even been read. If it was a doubtful act of sportsmanship on Escobar’s part, it was also a pretty good show of lucidity; Escobar never went down, was not ‘out’ on his feet, and knew where he was well enough to know he wasn’t the hometown fighter.

“Mayhem at the Mayborn’s” next two fights featured actual knockdowns, but no stoppages.

Frank W. Mayborn, after whom Temple’s civic center is named, was a publisher who founded four newspapers and a television station, in Counties Bell and McLennan – serving Waco, Killeen, Taylor, Sherman and Temple.

In honor of Mayborn’s reporting spirit, I queried the helpful Texas Commission of Licensing and Regulation about Saturday’s scores.

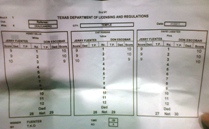

Don Escobar was ahead on all three cards – by scores of 29-28, 29-28 and 30-27 – at the time of Danny De Alejandro’s questionable stoppage. And as referee, De Alejandro was the man who’d collected each scorecard from its judge after every round.

Should the result be overturned? That’s a dicey proposition. Escobar deserved much better than he got. But so might Fuentes, if the fight were changed from “TKO-4 Fuentes” to “No Contest.” Fuentes, after all, had Escobar drunk with fatigue and punches, and there’s no telling what might have transpired in the fight’s last two minutes.

“But this is the kind of thing that gets me discouraged about the sport,” Escobar said afterwards. “I’ll always love boxing, but . . .”

As I strolled out the Mayborn Convention Center a couple hours later, still full with Opie’s Texas barbecue, having not had to make weight, and in a spectator’s euphoric trance after seven competitive matches – having collected nary a blow myself – I was past the vicarious injustice I’d initially felt for Don Escobar. I contented myself with a “that’s just boxing” for the nth time, the same way you would have.

But if we’re always going to say it like that, with such cynicism, are we right to continue encouraging others to pursue careers in our beloved sport?

***

A special note of thanks to Dr. Stuart A. Greene for the enjoyably concise history of Temple on his website, QualityDentistry.com.

Bart Barry can be reached at bbarry@15rounds.com. Additionally, his book, “The Legend of Muhammad Ali,” co-written with Thomas Hauser, can be purchased here.