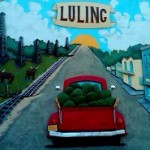

LULING, Texas – Here is a town that is home to 5,000 souls and represents the southernmost point of a golden corridor of Lone Star State cuisine. Luling to Lockhart to Spicewood, a 76-mile stretch that cuts through Austin and whose three towns’ populations total merely 26,000 people, somehow hosts six of the 50 best barbecue joints – according to Texas Monthly magazine – in all 268,580 square miles of the Republic.

Quite a feat, that. Smoked brisket, ribs and sausage are three things Texans know at least as well as their sports. “Good barbecue don’t need sauce,” they say down here, and it’s a fine way to keep straight the difference between Texas barbecue and its cousins in Memphis and Kansas City. El Paso, on this Republic’s western wing, does not have an entry on the cherished Top 50 list – the closest finalist is in Monahans, 250 miles away – but it has a whole lot of boxing fans.

Tuesday those fans learned they will be hosting an important event on June 16. Mexican middleweight Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. will face Andy Lee, an Englishman of Irish stock and Detroit residence, in a Sun Bowl fight that will decide both a title and the second-best man in the middleweight division.

The best man in the division remains Sergio Martinez. Much was made, Wednesday, of Martinez’s signing a one-signature rebuttal contract to make a match with the winner of Chavez-Lee in September. September, of course, is a decade away in boxing years.

Chavez will make his fight with Lee in June because Chavez’s promotional handlers at Top Rank believe he is ready. Ready as he’s going to be, anyway. A day quickly nears when Chavez will no longer be able to make the middleweight limit – that day, in fact, may have passed weeks ago, uncommemorated – and before Chavez can be steered away from Andre Ward at 168 pounds, the thinking goes, he’ll have to honor a few obligations in a middleweight division where he has already made six fights.

Chavez’s middleweight title is a gift from the WBC, a way of celebrating the legacy of Chavez’s dad, many argue, and once Junior gets in the ring with a real middleweight in his prime, a man like Lee, the end of this fraud will attain an exclamation point. Possibly. But Andy Lee has not quite raced through the sport’s best 160-pounders either.

Lee is the charge of celebrated trainer Manny Steward, and therefore, in the star system television makes of boxing, credited with recent wins over Troy Lowry (27-10) and Alex Bunema (31-7-2) and Saul Duran (40-19-2) in a somewhat exaggerated way.

Chavez’s trainer, too, is a star-system story that now feels overworked. Freddie Roach, who took on Chavez as part of a 2010 post-diuretic rehabilitation tour Junior’s people launched, has not altered Chavez’s fighting style in any permanent-looking way. But he has added the thorny Alex Ariza to Team Chavez. And somewhere between the potential drama of Chavez getting his coddled ass beaten and the palpable suspense of Chavez’s every trip to the scale, boxing fans have been enticed out of hiding.

Chavez, steadily becoming the most interesting man in the boxing world, doesn’t always fight in the United States, but when he does he prefers Texas (stay angry, my friends). Chavez is favored here and will be in June. Boxing has a rich history of hometown favoritism that television recently rediscovered in time to feign shock over it, because shock is entertaining.

Reporters have begun likening Texas to Germany, where crowd favorites enjoy spectacular advantages. Coincidentally, Texas and Germany are just about the last places on earth 40,000 boxing fans still congregate from time to time. All soliloquies to fairness aside, boxing is an often-filthy place that does not work as the branded and sanitized thing airless television studios endeavor to make of whatever their medium touches. Television wants known unknowns; boxing, bless its heart, gives them unknown unknowns.

Chavez will probably sell as many tickets on June 16 in El Paso as Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquiao combine to sell in Las Vegas, on May 5 and June 9 respectively, whatever television says about it. That used to be the measure of a star in prizefighting.

How did the rise of Chavez come to this? More naturally than anticipated, actually. Freddie Roach, speaking after his first abbreviated training camp with Chavez, which culminated in Chavez handling Irishman John Duddy, said Chavez came to him already understanding the geometry of the ring – from Chavez’s watching his father master it, and other men, as a boy. In a sport of time and space, Chavez’s geometric astuteness brought him into boxing 50 percent farther along than most.

Boxing is Julio Cesar Chavez Jr.’s native language. Roach may polish the grammar of some Chavez flourishes, but his primary function lies in discovering opponents’ sentence patterns, and then having Chavez recite them a few hundred times in training camp.

Andy Lee speaks boxing fluently, too. Immersion in Manny Steward’s curriculum ensured that. Lee does things with a technical proficiency Chavez usually lacks. But Lee also appears to remember learning the language of boxing, where Chavez could not if he wanted to. That’s a difference.

A palate for Texas barbecue is an acquired quality. Brisket can seem dry and sausage too spicy. And the absence of sauce on ribs can be, to the uninitiated, a touch unsettling. Texans, raised on brisket tacos and such, need no curriculum on barbecue, though, and as connoisseurs, need no directions to this city, Lockhart or Spicewood.

Texas fight aficionados will need no directions to El Paso in June. They know Chavez-Lee will be a good fight because Chavez does not make bad ones.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry