By Bart Barry-

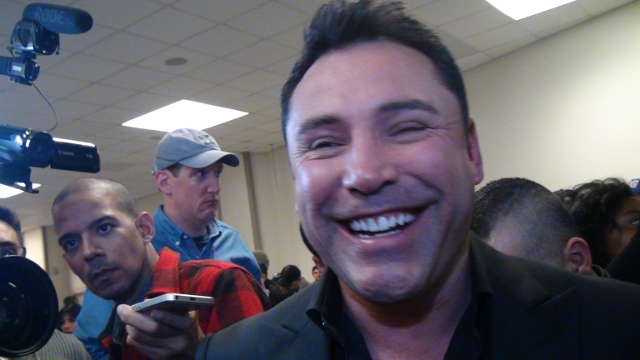

About 5 1/2 years ago, I wrote a column that treated Oscar De La Hoya and Todd DuBoef’s tactical use of candor and celebration of the free market and called it “In celebration of Oscar’s candor.” Today I rewrite it.

*

When Golden Boy Promotions’ Richard Schaefer revels in the free market’s amorality or Oscar De La Hoya discusses the defensive liabilities of any man he’s fought, put your smartphone down and immerse yourself in their wisdom. When they reverse roles, when De La Hoya gives you a stocktip or Schaefer talks combat, return to Facebook – unless you need a subject for your Monday column or a chance to opine generally about capitalism.

“We need to sign all the talent and get all the TV dates,” De La Hoya said last week to Broadcasting & Cable. “Then you can have your own agenda and have a schedule for the fans and the sport.”

While De La Hoya neglected to preclude that statement with a proper disclaimer – “as my friend Richard always tells me” – prizefighting’s most oleaginous figure was likely in the room with De La Hoya or else revising the interview’s first draft immediately afterward. In the few years since he began to conduct the orchestrations of Golden Boy Promotions, Schaefer has shown himself a shrewd strategist and singularly unlikable man. He thinks bigger than what small-potatoes promoters he occasionally mocks, seeing in their lack of national scope a want of desire, a want of ambition, a want, honestly put, of greed.

American English differs from Romance languages in its celebration of the word ambition – where a Peruvian called ambicioso would be properly insulted, inferring from the adjective he is naturally endowed with talents befitting a lower station than his aspirations’, any American called ambitious by a guidance counselor or prospective mate feels a burst of affirmation. Schaefer comes from a Swiss tradition that is neither American English nor Romance language, but he sees his success and others’ failures through a very American lens.

It is fair to imagine De La Hoya, a product of East Los Angeles and son of Mexican immigrants, enjoyed in his youth the company of exactly as many successful businessmen as young Schaefer befriended prospective prizefighters. They are anomalies to one another, then, and this benefits Schaefer more than De La Hoya.

De La Hoya’s path to success evinces an incredible combination of talent and luck. Fighters talented as De La Hoya are uncommon but do exist. None of them became the Golden Boy, though; to begin where De La Hoya began and arrive where De La Hoya arrived is probable as lightning hitting a lottery winner. To begin as a banker in Switzerland and arrive where De La Hoya found Schaefer is no rarity whatever. But De La Hoya probably doesn’t know this, and Schaefer, like all ambitious finance folks, is great with autobiographical musings of catastrophes overcome, extraordinary individual know-how, and foilings of what plotters would otherwise foil him.

It must rile Top Rank’s Todd DuBoef here and there to consider how insincere Schaefer is and how much money DuBoef’s stepdad, Bob Arum, failed to reap from De La Hoya’s 2007 match with Floyd Mayweather (another former Top Rank fighter). Not long ago, DuBoef floated an idea he called “brand of boxing” – a postmodern construct that celebrated postcompetitiveness. Unlike his stepdad, who wagers his credibility on three or four different fightcards annually and excavates rough jewels from mines in bad neighborhoods to present matchmaker Bruce Trampler for inspection, cutting and polishing, DuBoef occupies a time and land where prizefighting makes lots of money for the fortunate few who steer its enormous cash barge down an extraordinarily wide revenue river.

DuBoef prefers to maneuver round competitor islands and other nuisances, creating a television-production crew and handling pay-per-view cards in-house, where his stepdad prefers to go through them or over them or in any event at them.

“In boxing, virtually all of the publicity is keyed to a specific fight and, on a few occasions, to a specific fighter,” DuBoef said in June, lamenting boxing’s enduring competitive zealotry.

DuBoef’s model is nearer Schaefer’s model than Arum’s, and both Schaefer and DuBoef, faithful disciples of a system that coincidentally enriched them and assured them their riches evinced merit, not the luck of birthplace or parentage, likely wonder why Arum must do everything with such redness of tooth and claw, why he must be in constant and violent rivalry with some unfortunate or other to do his job effectively.

Bet De La Hoya understands.

While Arum’s success in life was perhaps more preordained than De La Hoya’s, the success of Arum as a boxing promoter was not. De La Hoya made combat with his athletic equals, men both interested in and capable of rendering him unconscious. Arum matched intellect, legal acumen and energy with his promotional equals, men both interested in and capable of his company’s ruination – including a once-a-century hustler like Don King. De La Hoya and Arum know lack and reflexivity; both men know the extraordinary effort, risktaking and luck required to attain momentum from a standing start, and they know how momentum feeds upon itself and moves money in hyperactive ways. Schaefer and DuBoef know a history of the modern free market and take as an article of faith it will reward those who respect it or love it praise it or whatever.

Schaefer’s future in boxing without De La Hoya, if ever they parted, would be but marginally less certain than DuBoef’s without Arum.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry