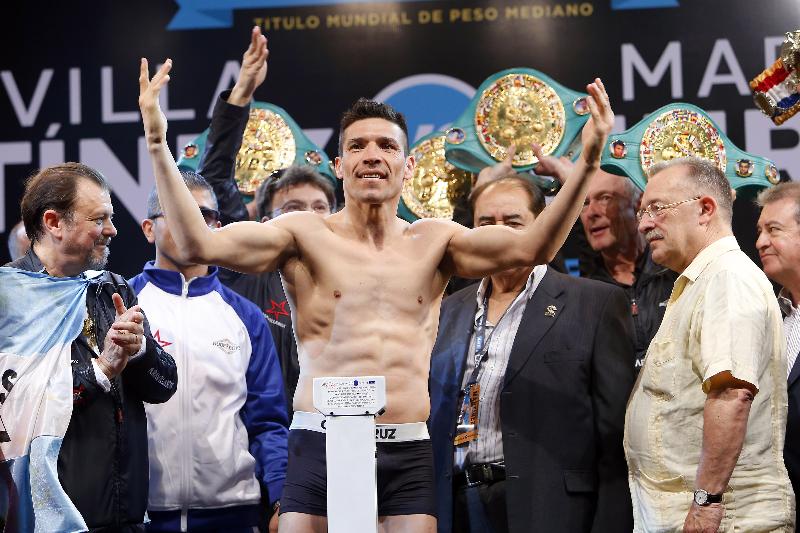

DALLAS – The career of middleweight champion Sergio Martinez will not end any better than our sport ends its every practitioner’s career, and that is an unfortunate revelation made obvious Saturday, when the Argentine Martinez made a homecoming title defense against Englishman Martin Murray and won a unanimous decision narrower than what its three rainswept judges, surrounded in a soccer stadium by 40,000 Argentines, tallied. The decision was not controversial because the decision was really not the point at all.

This was an exhibition, a career retrospective of Martinez’s works, and if it was rougher than planned for the homecoming champion, a scrap more than a celebration, it will not appear that way in the official record, which reads Martinez UD-12 Murray.

There is a level of introspection to Sergio Martinez that is rare among professional athletes in general and prizefighters in particular, perhaps because Martinez did not come to acclaim until he was well in his 30s, which is to impart Sergio Martinez knew himself, what he was and what he thought of what he was, before others could tell him what he was and what they thought of what he thought of what he was. There is a composure to Martinez, an affability, a willingness to show vulnerability – yes, that is the differentiating word: vulnerability – rare among professional athletes and all but impossible among prizefighters.

I spoke to him in January, nearer his penultimate fight than Saturday’s, and he was willing to describe, in surprising detail and self-deprecation, what discomfortingly intense moments ended his September match with Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. He treated rage-at-self and what drunkenness comes from sipping a homebrew of fatigue and abuse, and the revelatory fact nothing at the end went as he prepared it to go. Immediately after that I borrowed Thomas Hauser’s advice and asked Martinez what question he would ask those who ask him questions, his interviewers, if given the chance.

His answer was unique and personal: “What is the key to finding inspiration to write?” He spoke of what travails he encountered working on his first book, the hours cum days cum weeks of a blank page followed unexpectedly by a visit from the muse at three in the morning. Readers of this column will be unsurprised by how I answered: You must be willing to write garbage, Sergio, to keep your fingers flurrying on the keys, knowing your first draft is likely to be schlock anyway, and so why belabor it?

Saturday I was not in Buenos Aires, or Brooklyn, but rather at the final professional hockey game of the 2013 season in Lone Star State, this city’s Stars against the Detroit Red Wings, and I was not there to see either team or even the game of hockey, particularly, one I played through my adolescence, but rather an individual who plays the game close to perfectly as I have seen done: Pavel Datsyuk. His connection to Martinez is that Martinez is the professional athlete Datsyuk just edges on my list of favorite professional athletes. There is no one in any sport I appreciate more than Datsyuk.

I did not watch Saturday’s game, consequential as it was for the Red Wings franchise, but Pavel Datsyuk. When he was on the ice I followed him to the exclusion of the puck, and when he was not on the ice I was distracted, like other Texans, by campy fan-appreciation giveaways, shapely ice girls in lycra bottoms and a themeless potpourri of loud music. Datsyuk’s skating skills are now quietly eroded by knee surgeries; it is why he conserves energy by making large Cs more than large strides, more and more. His warmup stretching routine is novel for all the contortions it comprises, and his pregame skate was noteworthy for the number of times he lost edges, and the way he stood apart from the rest of the team, making passes to invisible marks on the boards, as his teammates swooped round him. While others collected pucks to fire at the Red Wings goalies – at them, not by them, by design – Datsyuk stood in innocuous places on the ice, passing the puck between the skates of his teammates to private spots on the boards.

Datsyuk is known in the league as “The Magician” for the innovative way he handles the puck, but that is missing the point of his greatness, which is a preparedness leavened by grit; no one makes it to the NHL without he can do things with a rubber disk and blacktaped blade of wood others appreciate in direct proportion to what hours they’ve practiced the same – which is altogether different from impressing naïfs and dilettantes, or Texans – but Datsyuk’s greatness is found in his individual battles with other men put on earth, they believe, only to play hockey. He defeats these men by being as good from either side of the puck, forehand or back, as no one before him has.

Martinez, for an enchanted stretch, bore a similarity to this. He stood before larger men and discouraged them, dis-couraged them, by causing their professionally aimed shots to miss by fractions of acceptable spaces in ways they could not predict. Martinez no longer has this capacity – as Martin Murray proved often, Saturday, but most especially in round 6, when Martinez invited Murray to discourage himself by missing Martinez repeatedly, and Murray repeatedly did not miss. Martinez hasn’t the technical perfection to perform adequately against larger men now that his reflexes have been taken by those larger men and what repairs to his body they’ve made necessary.

Saturday’s postfight happenings brought word Martinez will not return till April 2014. Better to call it a career, now, having filled a venue with his countrymen in a way no American prizefighter has done in decades.

Bart Barry can be reached at bart.barrys.email (at) gmail.com